Hi Everyone,

Due to some HTML problems on this blog, I have transferred to a new site, bringing along the same design and my favorite posts from here. Please click over and join the fun!

Thanks!

Monday, August 29, 2016

Monday, August 15, 2016

A Free Guide to Teaching Abroad (If I can do it, so can you!)

As some of you know, my husband and I spent two years teaching abroad in Bulgaria at the American College of Sofia. We learned so much, professionally and personally. At the time, moving abroad, in particular to someplace as unfamiliar as Bulgaria, was a huge stretch for me. But now that I've had the experience I would HUGELY recommend it for your consideration!

I have posted a guide to teaching abroad over at TPT that is really meant more as a springboard for your inspiration. It gives you the nitty gritty to get you started, but more than that, it gives you some reasons to get started. Maybe this time next year you'll be getting your classroom ready in Thailand, Paraguay, or Spain!

Peek at a few pages below, and then download it for free at TPT if you suddenly find yourself imagining life on the loose...

SaveSave

Sunday, August 14, 2016

Group Dynamics

As the school year approaches, I find myself re-reading the article I published last spring with NAIS. Giving some thought to how to set up your classroom as a safe discussion space for every voice is so worth the effort. Before launching in to literature circles, fishbowl discussions, Harkness, the socratic method, or any other discussion or small group pedagogy, please ask yourself, have I taught my students how to share this space? I hope the article below might provide some food for thought on this important issue.

Learning to Share:

Life Lessons in Group Dynamics

The only “D” I ever got in school was on a sixth-grade project that I felt was nearly perfect. I had conceived the idea, executed the idea, and taken my group along for the ride, as I had throughout elementary school. Always before, I had been rewarded with delighted teacher compliments and group-member approval. That pattern changed in one stabbing moment that I can still call up in a mental play-by-play.

My teacher pulled me aside after class to show me my grade on the “Create Your Own Religion” project.

So angry and confused, I didn’t know what to say; I listened as my teacher explained that here, at my new private school, things were different. My other group members had given me low grades for dominating the project.

My response: "Whatever." As I stormed out the door, I felt like someone had stolen something from me. In six years of education, no one had ever suggested any group skills for me to work on. No teacher had stepped in to teach me how to be a good listener or how to draw out other students. Rather, they had either leaned gladly on me to answer questions or ignored my fervently waving hand, calling on silent student after student to answer a question while we hand-raisers hovered above our chairs. Neither approach gave me much to go on when it came to group work.

So began a journey of frustration. Unsure of how to include others, I always felt disappointed when group projects were announced. Mostly, all it meant to me was I would have to do a lot of work, but be prepared to squelch my own ideas, the ones I was really excited to spend time on.

In my senior year, one of my best friends bravely confronted me after a seemingly insignificant argument.

"It just seems like you always think you are right. Please don’t be mad; I don’t want to fight."

I was devastated, but it was true, I did always think I was right. I was a top student, state Spanish award winner, State National History Day finalist, city essay contest winner, etc. But I didn’t know how to debate a point with my friend or hash out a project idea with a group. None of my teachers had taught me.

And so it went on. I did my best. I tried to learn to be a good listener, tried not to get attached to my own academic dreams during cooperative projects. But mostly I just hated those oft-repeated words, “Find a group and...”

Group dynamics didn’t really make sense to me until I became a teacher. In my first year, at a new faculty retreat, I received a handout about the Harkness method of discussion, invented and pioneered at Phillips Exeter Academy (New Hampshire) — and named after philanthropist Edward Stephen Harkness, a friend of Exeter Principal Lewis Perry, who in the 1930s donated $5.8 million to the school to change its pedagogy. As I read about the roundtable discussion method — in which the teacher acts as a guide for the discussion and works mainly to help students learn to ask good questions, share the air, provide support for their opinions, and navigate through distractions and accidental domination — I became more and more interested. I decided to launch a Harkness experiment in each of my four classes. We would try the method for one month, and see what we learned.

A lot, as it turned out. We learned the value of a quiet student’s opinion, when we finally heard it for the first time. We felt the tension in an awkward silence, as every student hoped I would jump in to save him or her. We ran head on against the obvious problem of a conversation in which one student speaks 25 times while others speak only once or twice. We learned that if there are no pauses for consideration, no one is really listening. We came to see that many opinions enrich the conversation.

Soon after that fruitful month, I signed up for the Exeter Humanities Institute and spent a week engaged in Harkness discussions alongside other teachers, learning the art of group dynamics simultaneously as student and teacher. I ended up dating and then (later) marrying a man who sat across from me at my second Harkness table there.

Back at my own school and completely converted, I introduced roundtable discussion to every one of my classes on the first day. I also began the “Harkness Breakfast Club” for teachers at my school, presenting and sharing the ideas from the conference with anyone who wanted to listen. I wrote an introductory article for the school’s wider association and presented to avid groups locally and then at the state convention of English teachers. Once I really understood the power of Harkness, I had no doubt that it, or some related pedagogy, had a role to play in every classroom. Whether using literature circles, fishbowl discussion, Socratic method, or some other similar tool, the point is the effort to truly teach students how to learn from each other.

I never taught another course without trying to teach my students about the feast of opinions and experiences available to them when they sat down at the table. In honors, regular, and I.B. courses, I tried to teach them how to listen and learn from each other. In courses I taught at home and abroad, I tried to share what I wish my teachers could have shared with me: how to be heard and how to listen at the same time, how to build a story that is everyone’s.

Part of Harkness is having a student observer sit back from each discussion and chart the progress of the group. I watched in amazement as observers presented back time after time, evermore nuanced as they shaped our evolution at the table. Observers quickly moved beyond charting the amount of comments and questions, considering such broad-ranging discussion elements as interdisciplinary connections, allusions to other works, and connections between points. They observed dynamics between the sexes, among groups of friends, between sides of the room. Since every student had a chance to observe over time, every student not only contributed to our conversation, but also added to our conversation about conversations.

“I think I’ve always been able to share my opinions, but I’ve definitely changed as a listener. I’ve learned how to pay attention.”

My teacher pulled me aside after class to show me my grade on the “Create Your Own Religion” project.

So angry and confused, I didn’t know what to say; I listened as my teacher explained that here, at my new private school, things were different. My other group members had given me low grades for dominating the project.

My response: "Whatever." As I stormed out the door, I felt like someone had stolen something from me. In six years of education, no one had ever suggested any group skills for me to work on. No teacher had stepped in to teach me how to be a good listener or how to draw out other students. Rather, they had either leaned gladly on me to answer questions or ignored my fervently waving hand, calling on silent student after student to answer a question while we hand-raisers hovered above our chairs. Neither approach gave me much to go on when it came to group work.

So began a journey of frustration. Unsure of how to include others, I always felt disappointed when group projects were announced. Mostly, all it meant to me was I would have to do a lot of work, but be prepared to squelch my own ideas, the ones I was really excited to spend time on.

In my senior year, one of my best friends bravely confronted me after a seemingly insignificant argument.

"It just seems like you always think you are right. Please don’t be mad; I don’t want to fight."

I was devastated, but it was true, I did always think I was right. I was a top student, state Spanish award winner, State National History Day finalist, city essay contest winner, etc. But I didn’t know how to debate a point with my friend or hash out a project idea with a group. None of my teachers had taught me.

And so it went on. I did my best. I tried to learn to be a good listener, tried not to get attached to my own academic dreams during cooperative projects. But mostly I just hated those oft-repeated words, “Find a group and...”

Group dynamics didn’t really make sense to me until I became a teacher. In my first year, at a new faculty retreat, I received a handout about the Harkness method of discussion, invented and pioneered at Phillips Exeter Academy (New Hampshire) — and named after philanthropist Edward Stephen Harkness, a friend of Exeter Principal Lewis Perry, who in the 1930s donated $5.8 million to the school to change its pedagogy. As I read about the roundtable discussion method — in which the teacher acts as a guide for the discussion and works mainly to help students learn to ask good questions, share the air, provide support for their opinions, and navigate through distractions and accidental domination — I became more and more interested. I decided to launch a Harkness experiment in each of my four classes. We would try the method for one month, and see what we learned.

A lot, as it turned out. We learned the value of a quiet student’s opinion, when we finally heard it for the first time. We felt the tension in an awkward silence, as every student hoped I would jump in to save him or her. We ran head on against the obvious problem of a conversation in which one student speaks 25 times while others speak only once or twice. We learned that if there are no pauses for consideration, no one is really listening. We came to see that many opinions enrich the conversation.

Soon after that fruitful month, I signed up for the Exeter Humanities Institute and spent a week engaged in Harkness discussions alongside other teachers, learning the art of group dynamics simultaneously as student and teacher. I ended up dating and then (later) marrying a man who sat across from me at my second Harkness table there.

Back at my own school and completely converted, I introduced roundtable discussion to every one of my classes on the first day. I also began the “Harkness Breakfast Club” for teachers at my school, presenting and sharing the ideas from the conference with anyone who wanted to listen. I wrote an introductory article for the school’s wider association and presented to avid groups locally and then at the state convention of English teachers. Once I really understood the power of Harkness, I had no doubt that it, or some related pedagogy, had a role to play in every classroom. Whether using literature circles, fishbowl discussion, Socratic method, or some other similar tool, the point is the effort to truly teach students how to learn from each other.

I never taught another course without trying to teach my students about the feast of opinions and experiences available to them when they sat down at the table. In honors, regular, and I.B. courses, I tried to teach them how to listen and learn from each other. In courses I taught at home and abroad, I tried to share what I wish my teachers could have shared with me: how to be heard and how to listen at the same time, how to build a story that is everyone’s.

Part of Harkness is having a student observer sit back from each discussion and chart the progress of the group. I watched in amazement as observers presented back time after time, evermore nuanced as they shaped our evolution at the table. Observers quickly moved beyond charting the amount of comments and questions, considering such broad-ranging discussion elements as interdisciplinary connections, allusions to other works, and connections between points. They observed dynamics between the sexes, among groups of friends, between sides of the room. Since every student had a chance to observe over time, every student not only contributed to our conversation, but also added to our conversation about conversations.

Before a presentation to other faculty members, I polled my students anonymously about their experiences. “I think I’ve always been able to share my opinions, but I’ve definitely changed as a listener. I’ve learned how to pay attention,” wrote one student. Another experienced a different kind of transformation: “I have changed. I seem to like to talk a lot more than I thought I would. Harkness has allowed me to gain confidence in myself and what I believe is right.”

The beauty of these responses is that they show the connection between the students’ different kinds of growth. As some students learn to listen, they enable others to believe in themselves. As some students learn to speak, they enable others to widen their understanding.

For me, watching my students learn how to have a conversation was sometimes hard. I struggled alongside students who had been trained to believe domination was success for half their young lives.

In one memorable senior English elective, there was an obvious barrier within the group between the dominators and the quiet students from the first day. Two students were taking the course alongside an AP Language elective; they had registered for two English courses because literature was their passion. Ten students were taking the course because their grades weren’t high enough to get into the senior AP course. For a while I listened as the conversation drifted back and forth between the two strongest students, doing my best to encourage the quieter students. I tried various tricks to prompt a shared discussion, but my usual repertoire did not pay off. Finally, I came up with a challenge, that everyone in the course would get a free “A” grade in my gradebook if we could have just one discussion in which everyone spoke.

It took us a while. Several quiet international students, who had never become fully comfortable with speaking English, really struggled. We kept trying. Eventually everyone began to participate. In private conversations with the two dominators, I worked with them on the idea that if they could back off, someone else would simply have to step in and carry more of the weight of conversation. We would not have 45 minutes of silence. I shared my hope that we would learn more with 12 people’s thoughts than with two, no matter how easily commentary might come for those two. Both seemed skeptical that such a conversation would ever take place.

Finally, we had a discussion in which two previously silent students stepped to the fore. The ice broken, everyone began to speak. The conversation was unlike any before, unexpectedly beautiful. One of the dominators, smart and talented, the school president, stayed after to talk to me. She started to cry.

“I really didn’t think they would say anything,” she said.

I completely understood how she felt. It was a lesson she was learning years ahead of me, and I hope it was worth the pain of learning it. I believed, as we talked, that she would carry out of that day a new kind of self-knowledge, a knowledge that would help her in business meetings, conversations with family, college projects, community gatherings. Understanding the power of group dynamics transcends the classroom for anyone who lets it.

When I introduce the concepts of roundtable discussion and group dynamics now, I feel they make up the most important lesson in my classroom: how to share ideas with others. To me, this is more important than the analytical essay, more important than SAT vocabulary, more important than giving a good speech. What can be more fundamental than conversation?

These days, I unconsciously notice the group dynamics wherever I go, and often wish I could discuss them with groups of adults in which some have never learned how to listen and others don’t feel heard. No doubt I still fall into my old dominating ways sometimes, but at least they are just that now, my old ways.

I am taking some time off from teaching, but a recent conversation with a ninth-grader I know brought it all back. He felt trapped as a silent onlooker in one of his classes, wondering how to break into the conversation.

“There are these two girls who always talk. And it seems like the teacher looks at them to answer every question. I used to say a lot at my old school.”

I gave him all the strategies I could think of to help him enter the conversation, and thought about approaching his teacher to share some of my experiences.

Suddenly I wished to be back in the classroom. Finally, a decade after graduating from college, I know exactly what my role is in a group. To make sure everyone has a role. To facilitate the creation of a complex story, made up of many voices, every day.

____

____

Saturday, February 6, 2016

Social Media Advice for Small Businesses: Reading Gary Vaynerchuk

I first saw Gary Vaynerchuk when he was interviewed on Marie Forleo's youtube show. Here's the episode:

I found him compelling. So I ordered his latest book, Jab, Jab, Jab, Right Hook to inform my Teachers Pay Teachers social media decisions. It turned out to be a good call, and here's why.

Vaynerchuk breaks down the complex realms of social media effectively in this book.

One of his main messages is that each category of social media requires a different strategy, and that that strategy can be effectively learned and capitalized on. He goes through the major social media outlets (Twitter, Tumblr, Facebook, Pinterest, Instagram, Vine) and shows a variety of examples of how people are marketing there - both effectively and ineffectively. He breaks down each colorful example in a brief analysis.

His second main message is that in the current sharing economy, you need to share ideas, fun, freebies, comedy, relaxation, etc. via social media WAY more than you market. As a brand, the idea is to become a positive association for people rather than always trying to sell them something. Each joke, meme, link to a great article, freebie, etc. that you share on social media is essentially a "jab" so that when you want to reach people with a really great product, they will actually care about your "right hook."

The book is very readable and has a lot of quick takeaways. It gives you a sense of when to post things, how to post things, what to post, etc.

It caused me to immediately change my strategy on my Facebook when I realized that their Edgerank system was preventing most of my posts from even being seen by my followers, since I wasn't getting enough shares, comments, and likes. It caused me to immediately change my strategy on my Pinterest, when I realized that my educational brand could support pages about my other interests, like cooking, travel, design, etc. It caused me to start a new Twitter account, which I am actually enjoying now.

I would definitely recommend this book to those, like me, who are learning how to run a small business through Teachers pay Teachers.

5 Tips from the many I learned from the book:

1. Focus on getting your posts liked, shared, and commented on on Facebook.

2. Share a lot of ideas and freebies on social media for every time you post a link to a product or tout a sale.

3. Engage others in a meaningful way on social media, showing your expertise in your field.

4. Don't be afraid of new realms of social media. If only teenagers like it now, it may well be the next big thing! Wading into Tumblr, Vine, etc. can only help your brand in the long run.

5. Always caption your Pins with something great, and develop a big variety of boards on Pinterest so you bring in a wider variety of people to your brand.

Saturday, January 30, 2016

The Novel Collage: 1984

I love doing cross-curricular projects that connect literature and art. Throw in modern connections with a collage angle and you've got me hooked. Every year when I assign the 1984 collage project, I love the results. They make for such an interesting (if terrifying) classroom display. The connections students make between modern media and the ideas embedded in the novel are powerful, and since they can choose to do it with computer graphics or good old scissors and glue, I don't lose that element of the class that always claims to "just hate art stuff" as easily as when I take out my box of art supplies.

Here are some of my favorite results:

Here are some of my favorite results:

Do you do any art projects in your English classroom? How do you go about attracting the part of the group that always thinks art is for kindergarten?

Tuesday, January 26, 2016

Small Groups.. friend or foe? + FREEBIE

As a student, I HATED group projects. Not only did I end up doing all the work, I usually got blamed by my teachers for not being more inclusive of other students. But did my teachers TEACH me how to be inclusive? Or how to collaborate effectively? Nope.

As I look around the pedagogical world for good advice on group work, I mainly see the idea of using roles. Sure, one person can get materials, one can ask questions, one can take notes. This is somewhat helpful, especially for younger kids. But as kids get older, they are basically left to figure out group dynamics on their own, and my experience was that this really doesn't work.

When I assign major projects, I often give students the option to work in groups or alone. But sometimes that isn't possible, as with a project to perform a scene from a play. And I also want to encourage the students who dislike group work to dabble in it, because heaven knows, they are going to see a lot of group scenarios in their lives. Board rooms, faculty meetings, family dinners, PTA gatherings - group dynamics are everywhere you turn as an adult! So I feel like giving my students some clues along these lines is a really important service.

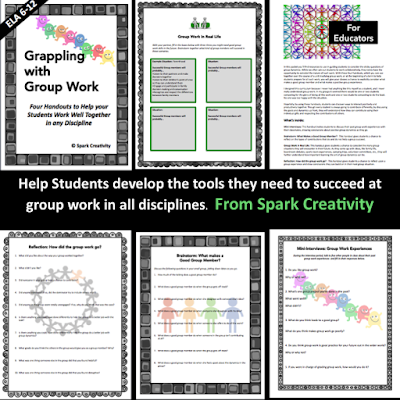

In an effort to condense my thoughts and experiences on group work into a curriculum packet for students, I created these handouts:

As I look around the pedagogical world for good advice on group work, I mainly see the idea of using roles. Sure, one person can get materials, one can ask questions, one can take notes. This is somewhat helpful, especially for younger kids. But as kids get older, they are basically left to figure out group dynamics on their own, and my experience was that this really doesn't work.

When I assign major projects, I often give students the option to work in groups or alone. But sometimes that isn't possible, as with a project to perform a scene from a play. And I also want to encourage the students who dislike group work to dabble in it, because heaven knows, they are going to see a lot of group scenarios in their lives. Board rooms, faculty meetings, family dinners, PTA gatherings - group dynamics are everywhere you turn as an adult! So I feel like giving my students some clues along these lines is a really important service.

In an effort to condense my thoughts and experiences on group work into a curriculum packet for students, I created these handouts:

I've decided to give them away for the next week so teachers who want to can try them out in their classrooms. I'm hoping to get some product feedback on this new packet. I think it can really help a lot of students with something that was always hard for me. Please go and download them, then if you get a chance, leave a review to let me know what you think!

For more group work ideas, check out a growing collection of resources on my Pinterest Small Groups page.

Sunday, January 24, 2016

TPT Tip Series: Clipart!

I remember when I was a new teacher in California, searching anywhere and everywhere for ways to improve my classroom teaching. In the discount bin of my local school supply store I found two huge CD Rom packs (yep, that's right, CD Roms) labeled "10,000 Clipart Images" and "10,000 Fonts." So of course I bought them. And proceeded to dazzle my students with Halloween-themed fonts, fun headers, etc. Putting together handouts was so much more fun with good graphics, and as a visual learner myself, I felt like I was giving my students a gift by presenting the information in an attractive way.

Fast-forward ten years and one of the first pieces of advice I read for new TPT sellers was to "invest in good clipart." Pshaw, I thought, there's gotta be a go-round. And there was. Pixabay. I developed my initial products with fun free clips from Pixabay, searching for whatever theme I came up with.

But Pixabay, though free, had its limits. I began to shop around TPT looking for clipart freebies. And I found quite a few. You will too, if you look. That's when it's time to start a "Graphics By" section on your advertising page at the end of your product. Wait, you don't have an advertising page? Get one! I put this page at the end of all my products, just adjusting the graphics section to feature whoever's clipart I am using. This is a great way to share your social media information with other teachers, and to give them an idea of what else is in your store, as well as to show who is designing your art and give them credit. Just design a powerpoint with a basic title page at the front that you can redesign for any product, some blank pages in the middle, and this at the end and save it "TPT Template" on your desktop. Then you don't have to redo everything every time you start a new product.

After a while though, even clipart freebies and Pixabay weren't enough for me. I wanted to find some lovely clipart that I could use in a range of situations for older kids. After a lot of searching, I did. My favorite artist by far is Paula Kim Studio, so I'm going to go ahead and give her a shout out here. She makes beautiful designs, and she doesn't even demand a certain way of citing her in your products. Once you buy them, it's up to you whether or not to cite her store in your final page.

Combining freebies, Pixabay, the small variety of fonts and colors available in Powerpoint, and several packages from Paula Kim and a few other clipart designers, has allowed me a great deal of graphic design freedom in my store, though I've probably only spent about $30 on clipart. You don't need a new package of clipart for every product you make. Just invest in some nice borders, papers, labels, and banners. Voila! Professional looking cover pages and lovely internal art. You can see my style by visiting my Spark Creativity Pinterest page where I put up all my products.

Wednesday, January 20, 2016

PBS, A Valuable Resource!

PBS, it's not just for Downton Abbey. Though I must say, I'm pretty excited for the new season.

But I'm also excited about PBS's educator's resources. One that I have regularly used for teaching Mark Twain is the Mark Twain Interactive Scrapbook.

But I'm also excited about PBS's educator's resources. One that I have regularly used for teaching Mark Twain is the Mark Twain Interactive Scrapbook.

The clickable links guide students through a ton of great primary sources. It's perfect for a web quest or to help you introduce Mark Twain or Huck Finn via a projector or Smartboard.

PBS has lesson ideas, videos, and fun tools like the Puzzle Builder, Quizmaker, and Digital Storyboard. Go check it out!

Tuesday, January 19, 2016

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)